Much of the discussion surrounding very young children’s media use is often of a protectionist nature against negative effects, or conversely proselytizes educational benefits of digital technology. As noted in part one of this post, rich insight can be gained by framing the discussion rhetorically, specifically analyzing the domestic uses of technology in the form of parent-posted YouTube videos of babies and toddlers using the iPhone, iPad, and iPod Touch.

***

Method

A purposive sample of 85 amateur YouTube videos was selected, accessed from October 15 to November 26, 2010, and originally uploaded between July 6, 2007 and October 31, 2010. These clips were located via searching for either the terms “baby,” “babies,” “toddler,” or “toddlers” in combination with either the words “iPhone,” “iPad,” or “iPod Touch.” Of parents who explicitly noted their child’s age, the range was from 2-months to 3-years-old.

Three main elements of each YouTube video were considered as text for the rhetorical analysis: the audio-visual of the YouTube clip itself, the title that the user gave to the video, and (if provided) the description for the video that the user posted in the provided space on screen below the clip. The videos mainly featured American parents and young children, but also included a number of families from Europe and Asia, providing some geographic, cultural, and ethnic diversity. Most of these videos were filmed at home, with a few shot at the Apple store. Few of the various textual sources provided information about what recording device was used to shoot the video.

Results

Three main categories of parents ’ construction of the image of their children emerged from the sample: (a) children “acting their age” (b) children as exceptional or “acting above their age” and (c) Apple technology as exceptional. The videos in which children were “acting their age,” parents made no claims about the child being exceptional or advanced for their age. For the videos in which children were presented as “acting above their age,” parents expressed in various ways that their child was more exceptional than other children, than other adults, or were exceptional at either explicitly or implicitly promoting Apple products. The other common theme was of placing a strong emphasis on the technology itself as being transformative. Note that some individual videos presented multiple themes, and are not restricted to one category or another.

Children “Acting Their Age”

Many videos presented children’s interactions with Apple technology as “cute.” Humor was primarily derived from bodily functions, parental experiments with very young children’s behavioral temperament, and babies using the iPad as a “mirror.” The device served as both a reflective surface, but also as a reflective tool for viewing pictures and videos of both the babies themselves and other babies as well.

There were a number of video recordings shot from the iPhone while the device was in the child’s hands, the camera was on, and the camera was facing the child. Nearly all of the videos shot in this manner featured a baby attempting to lick or put the iPhone in his or her mouth (one entitled “Baby eats iPhone”). Another video showed a mother trying to dissuade her child from putting the mother’s iPod Touch directly into the boy’s training toilet (entitled “iPotty training”). Humor was also derived from the bodily function of a child sneezing onto an iPad and rubbing the snot on it (entitled “KID SNEEZES ON IPAD HILARIOUS!!!”). Another video was entitled “Cute 8 month old baby on the toilet potty training w/ iPad.” The children in these videos were primarily interacting with the physical hardware and not manipulating the device’s software.

Another recurring theme was parents using the Apple device as a prompt for behavioral experimentation with their young children. Some prompts were more explicit than others. For example, in one video, a parent positioned two babies to sit next to each other, one holding an iPhone and the other child looking on. The baby holding the iPhone threw a fit when the other baby attempted to touch the device. In other cases, parents themselves used the device to solicit a desired response from the child. For example, some videos showed babies crawling to iPads that their parents had purposefully put just out of reach of the child, in order to prompt their child to crawl towards it. In one entitled “Luke walking to the IPhone,” the iPhone’s forward facing camera recorded the child walking towards the device. While some parents attempted to evoke forward movement such as crawling or walking, other parents used the device to pacify their child and stop them from crying. There were videos of babies crying and caught on video being instantly quelled by having an Apple device put in front of them. Conversely, videos like “Baby iPhone Addict” and “iPad Toddler Tantrum” demonstrated a very young child crying upon having an Apple device taken away from them.

One video (above) in the sample was different from the rest in that the video showed a parent supporting their child’s use of an iPhone application in a way that was developmentally prosocial in terms of communication style but antisocial in content. That video was entitled “2 year old using iPhone. Shotgun by a 24 month old baby boy!” It showed a father providing positive physical and verbal feedback to his child’s simulated gunplay with the “Shotgun” iPhone app. In the video, the father asked the child “What’s that?” pointing to the icon for the “Shotgun” app. The baby responded “Pow pow!” and retrieved the Shotgun app, to which the father asked, “How do you make it go ‘Pow pow’?” The baby then shook the iPhone in a forward motion and the phone made a lock and load sound. The boy then smiled and said “Pow pow!” to which father went “Alright!” The content on the Apple devices allows for multiple types of learning as scaffolded by the parent, learning content that is not necessarily prosocial.

A number of babies also used the Apple devices for looking at still pictures of themselves or of their families, or videos of YouTube clips of other babies. In terms of babies watching YouTube videos, in one video a child watched the aforementioned viral video “Charlie bit my finger – again!” Another video shows a baby watching a video of a laughing baby on her mother’s new iPad. The child is transfixed and giggles in response to the giggling in the video. In another clip entitled “Baby Sadie watches Babies Trailer on iPad,” the parent describes the video as “Here’s my 6 month old daughter watching the Babies Trailer on a new iPad. Talk about multi-layered marketing.” Babies, a 2010 documentary looking at the lives of four babies from around the world, provides the opportunity for the child to mirror another very young child’s emotions and facial expressions. Meanwhile, the parent’s uploading of the video serves in some ways as an advertising tool for both the movie and Apple within the YouTube space.

Children as Exceptional or “Acting Above Their Age”

Another type of video demonstrated parents fetishizing their children’s perceived extraordinary nature, whether their children were extraordinarily intelligent and/or mature. Three main themes were identified for ways in which parents promoted their child’s exceptional nature, 1) in terms of their child being smarter than other children, 2) being smarter than the general population or those much older, and 3) of their children being exceptional advertising vehicles for Apple products, as a briefly alluded to in the earlier example of the baby watching the Babies trailer example.

1) Children as more exceptional than other children.

Various parents promoted the rapid pace of their child’s perceived mastery of the Apple devices. Many indicated that their young child “instantly” learned how to use the gadget. One parent wrote that their 20-month-old child “mastered the iphone months ago.” Another described their child playing a piano iPad app (of which there were many babies playing piano apps videos) as a “Mozart baby,” invoking the Baby Einstein moniker and the much-debated link between classical music and the intellectual growth of very young children. Another mother wrote of her child’s ability to distinguish between single- and multi-touch devices, “She even knows that her other fingers shouldn’t be touching the screen.” Quite a few videos also demonstrated parents marveling not over their child’s navigation of the specific applications, but rather their child’s ability to “unlock” the iPhone. Many of the children in these videos were praised for the ability to do so by their parents. It is unclear from these videos if the child also understood the non-digital key/lock referent.

Some of the videos were more explicit about directly comparing one’s child to other children. Through clip titles and descriptions, a large number of videos in the sample demonstrated parents labeling their child as the “world’s youngest” or “the real youngest” iPad, iPhone, or iPod Touch user or as an “iPhone kid genius.” Some parents also demonstrated self-awareness to this hyperbole, as one father noted of his child, “He’s a genius. (Well, at least his dad & mom think so.)” Other parents evoked norms by describing their children as “more than average.” Consider this video description: “My sweet little boy is just an average boy doing just a little bit more than the average kid to be independent more and more each day.. Mind you he is just a one yr old boy.. (He first used the ipad when he was 16 mos old) now i wonder if he is the youngest ipad user today.. =)”. While the example initially validates normativity, in increments the parent represents the child as above the norm, from an “average boy” to the “youngest ipad user today.” Some videos ironically juxtaposed normativity and exceptionality. One video, described as “Three-month old prodigy Ilan Peter Oren performs selected works on the iPad piano” was introduced by an iMovie title screen with a red curtain that parts, flickering candelabras, and a gothic-style lettered title “Great Performances.” This polished production value is purposefully contrasted with the child’s limited range of motion as well as his spitting up about 50 seconds into the one minute and 25 second video.

2) Children as more exceptional than adults.

Some parents positioned their children as exceptional by deemphasizing their own role in their children’s learning, as well as generally comparing their children to the older general population. In a few cases, parents asserted their child’s exceptional nature in relation to not needing intervention from adults in order to master the Apple devices. As one parent described their video, “My son has now learned how to turn on the iPhone, unlock it and flip through his favorite photos. He hasn’t had much coaching to learn this. He just watches me using it.” The parent downplays their own active teaching role in favor of promoting their child’s observational learning. Independence was a popular theme. Another parent wrote, “He knows how to operate the ipad on his own.. From turning it on, going to the menu, choosing the applications that he likes and playing with them.. =) He is all on his own when he uses the ipad and alot of other things actually.. he is quite an independent kid!” This is not to say that parents who described their children as exceptional did not also acknowledge their child’s limitations. For example, as another parent described, “we just wanted to show everyone that even a 22 month year old baby girl who can barely even talk can play a sophisticated device like the apple ipod touch. she learned this by just watching us play games on the ipod touch. i had to record the video behind her so she does not know she was being recorded because if she knew she would have paid attention to the camera.” In another video, an edited short movie entitled “iPhone Baby PWNAGE!!!” a baby shows a befuddled father how to turn on his iPhone. There was an interesting dynamic in these videos between attributing the child’s exceptional nature to the parents or the children themselves.

A number of videos also contrasted the child’s dexterity with the devices to the general population. Unlike non-experts, one child “knows how to use the phone like a pro.” One tongue-in-cheek video was subtitled “If i phone, uCan too!” which the user described as “How to use the functions on your iPhone” by her 1-year-old daughter. In another YouTube clip, a toddler unlocked an iPhone and wove it around as he danced and bopped around to James Brown’s “Living in America” in his carpeted home hallway in front of a laundry basket (entitled “iPhone: You’re never too young for one”). The child was thus framed as enjoying the device in a way that “you” might. Additionally, in the aforementioned Shotgun app video, the parent compares the child to other relatives, noting in the description, “My son loves my iPhone. He is more efficient at it than his grandmother.” These videos compare and contrast their child to the population-at-large.

3) Children as exceptional advertising vehicles.

Another recurring theme was children personifying and promoting the Apple commodity. Some videos were explicitly promotional, such as the testimonial clip entitled “Baby and the iPad – Uzu App Review (by a 4 month old).” In the video description, there was a link to the mother’s own blog of digital media reviews. And at the end of the clip, there was also an on-screen caption (“2 slobbery thumbs up for the Uzu app”) placed over a still frame of the smiling child. A description accompanying another video linked to the iTunes page for the app being demonstrated by the child, and claims that the app would “make your babies even cuter!!!”

While some videos promoted apps, which are generally produced by companies other than Apple, some of the videos presented children mimicking the Apple brand. One video was actually a 30-second mash-up of one of the original existing Apple commercials for the first generation iPhone and home footage of a parent holding the iPhone above their baby like a crib mobile. The re-recorded vocal track played over the commercial’s iconic acoustic guitar track. The ad copy was modified to say, “With the iPhone, you can listen to your favorite songs. You can even check your email. Not only that, you can surf the Internet and watch your favorite movies. Even better, the iPhone is now a pacifier for your baby.” And in perhaps the most explicit Apple fan video, entitled “Baby Steve Job’s iPhone”, a 2-year-old dressed up as Steve Jobs for Halloween, in Jobs’ uniform of high-waisted jeans, a belt, and a black turtleneck. The child also held the plastic case and cardboard insert replica of the iPhone that generally comes with the phone’s packaging.

Apple Devices as Exceptional

Some videos more than others fetishized the iPad, iPhone, and iPod Touch. This praise manifested in two ways: one, in terms of displaying the newly purchased Apple device as a display of wealth, and second, in terms of the benefits of the technology for children with disabilities.

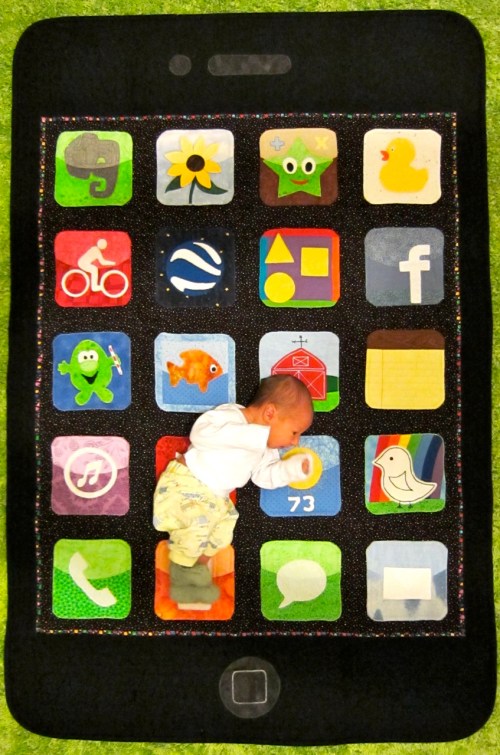

By posting a video of the child playing with the newly acquired device, a number of parents asserted their socioeconomic status. The chronologically earliest videos in the sample were created shortly following the release of the first generation iPhone, and there was a large spike in sampled videos produced in early April 2010 following the release of the first generation iPad. Some videos featured parents or children opening the box and removing the item from its original packaging. One video (above) displayed a father performing this action, followed by positioning the iPad into his baby’s arms as if cradling the device. This ritual seemed much like the modern American traditional photo of children taken in professional photography studios in homes or at Sears, in which the child holds an arbitrary stuffed animal or toy like a prop, as the child is too young to understand the item. Other parents distinguished that this was a gift unlike any other gift, as one described, “My child loves the iphone more than any of the 100 toys we bought him.” In these case, the handheld Apple devices are tender gifts for the child to grow into, and love much as the parent loves it. As many parents keep such items as an iPhone or iPad physically close enough to constantly touch, demonstrating their child’s proficiency with these singularly significant devices reflect the parent’s physical and emotional bond between and betwixt their child and their devices.

Other videos focused on the transformative properties of the Apple devices for children with special needs. Consider the following video description about one parent’s son:

His speech, understanding, word recognition, and even hand eye coordination have improved within just a short while!! I am so amazed and thankful for this amazing learning tool that my son has! I wanna say thanks to Apple and all those that have given my child such a head start in life with this amazing instrument! My son can read tons of words now, he knows every animal and dinosaur and he just turned 2 years old!!!! If you have a child around 2, don’t rob him/her of knowledge, go buy him/her an iPad!

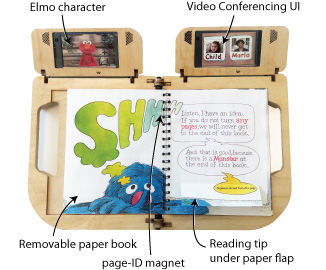

Some of these videos were intended for the audience or community of other parents of other children with disabilities as a form of social support and testimony about the devices. These videos primarily featured children with cerebral palsy and autism using the iPad, and on the whole these children tended to be a bit older in age than the foci of analysis. These videos merit a richer analysis than. For example, one mother posted a series of videos of her son’s use of the iPad, which she described as a “tool not a toy.” She described during one such video how “This time I made it more challenging for C. Using the TapSpeak app like a Big Mac switch he used the iPad as a communication tool/AAC device instead of a toy and was much more satisified.” This parent did not seem to express the sentiment that the technology was more exceptional than her child, but rather that the technology was so powerful because it gave her child the opportunity for self-expression.

***

Through a textual analysis of the audio-visuals, video titles, and video descriptions, these clips help us understand the role communication technologies play in the interactions between a select demographic of mostly US parents and very young children. In my next post, I’ll discuss how these videos are parents’ public displays of their own and their child’s economic, social, political, and cultural capital and the relationships embedded in these displays. In turn, the public presentation of the digital YouTube asset speaks to children’s current and future value, visibility, agency, and identity within their families and to a commoditized society.